Shadow work is not a self-help trend—it is a foundational psychological practice rooted in the analytic psychology of Carl Jung. At its core, shadow work addresses a fundamental truth of the human psyche: what we refuse to acknowledge within ourselves does not disappear. Instead, it operates unconsciously, shaping our emotions, behaviors, relationships, and life choices from behind the scenes.

Modern culture often encourages relentless positivity, emotional control, and personal branding. Within this framework, uncomfortable emotions and socially inconvenient traits are quickly suppressed or reframed. Yet the psyche does not operate according to social preference. What is denied consciousness does not dissolve; it relocates to the unconscious, where it exerts influence without consent or clarity. Shadow work exists precisely to interrupt this process.

Much of what people experience as self-sabotage, chronic emotional reactivity, or a persistent sense of inner conflict originates not from a lack of willpower or insight, but from disowned aspects of the self. These parts do not disappear simply because they are inconvenient. Instead, they surface indirectly—through projection, impulsive behavior, emotional numbness, or repeating life patterns that seem resistant to conscious intention.

When these unconscious elements remain unexamined, they exert influence autonomously—often in ways that feel confusing, disproportionate, or destructive. A small criticism triggers disproportionate shame. A minor rejection feels catastrophic. A familiar relational dynamic repeats despite conscious resolve to change. Shadow work offers a structured means of bringing these hidden forces into consciousness, where they can be understood, integrated, and ultimately transformed.

The Shadow Self in Jungian Psychology

In Jungian theory, the shadow refers to the aspects of personality that the conscious ego does not identify with. These traits are often shaped early in life, as we learn which emotions, impulses, and qualities are rewarded or rejected by our environment. Family systems, cultural norms, religious frameworks, and early attachment experiences all contribute to what becomes acceptable—and what does not.

Over time, unacceptable qualities—anger, vulnerability, dependency, ambition, sexuality, even creativity—are pushed out of awareness to preserve a coherent self-image. This self-image, or ego identity, is not inherently false; it is simply incomplete. It reflects who we were allowed to be, not the full range of who we are.

Importantly, the shadow is not synonymous with what is “bad.” It contains everything that has been exiled from consciousness, including positive capacities that never found safe expression. Confidence may be buried alongside arrogance. Tenderness may be suppressed alongside fear. Assertiveness may be hidden because it once threatened belonging.

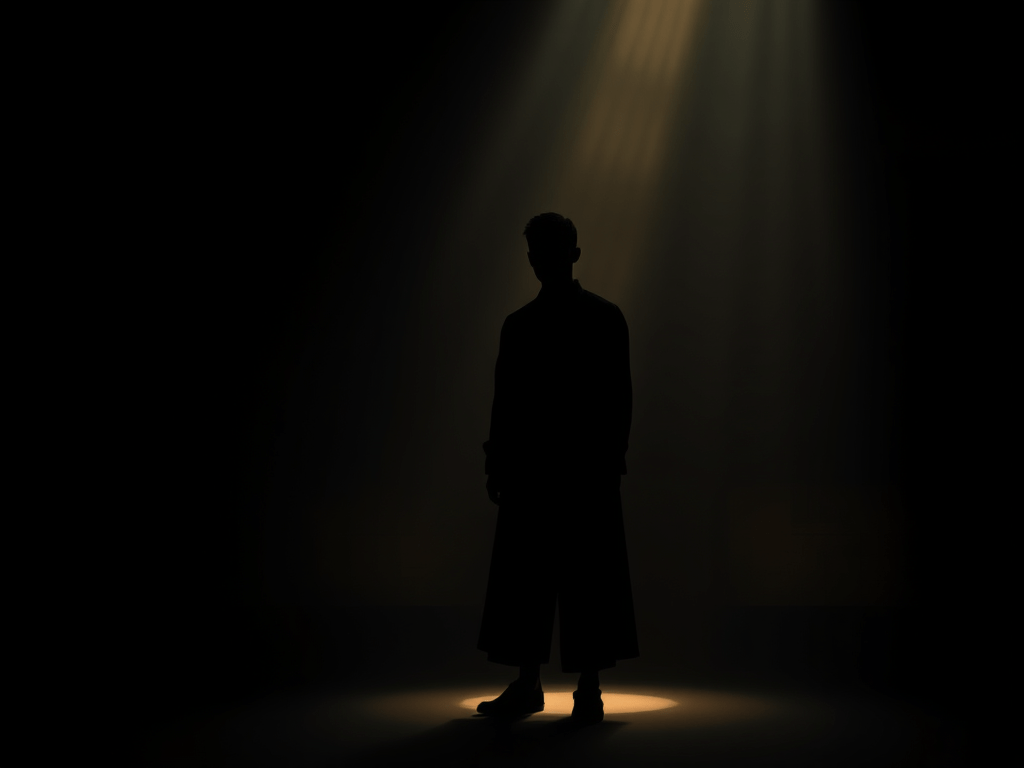

The problem arises not from having a shadow, but from being unconscious of it. Jung famously warned, “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.” In this sense, fate is not a mystical force, but a psychological one—the repetition of what has not yet been integrated.

Shadow work is the disciplined practice of turning toward these unconscious elements with curiosity rather than moral judgment. Through this process, the individual moves toward psychological wholeness—what Jung termed individuation. Individuation does not mean perfection or purity. It means becoming more fully oneself, less fragmented, and more internally aligned.

Entering the Work: Creating Psychological Safety

Effective shadow work begins with containment. The unconscious does not yield its contents through force, confrontation, or intellectualization. It responds to safety, patience, and sustained attention. Without a stable container, attempts to explore shadow material can feel overwhelming, destabilizing, or self-punitive.

Whether through reflective journaling, meditation, psychotherapy, or intentional solitude, the psyche requires a stable internal environment in which difficult material can emerge without overwhelming the ego. Silence and slowness are not luxuries here; they are prerequisites. Shadow material often surfaces subtly—through images, emotions, bodily sensations, or fleeting thoughts that require space to be noticed.

Setting a clear inner stance is essential. Approaching the shadow with condemnation only deepens repression. Approaching it with curiosity signals readiness for integration. The difference is subtle but profound. Judgment closes the door; curiosity opens it.

A simple intention—I am willing to see what I have not yet seen—can establish the psychological conditions for meaningful insight. This stance does not demand immediate understanding or change. It asks only for honesty and presence, which is often enough to begin.

Emotional Triggers as Portals to the Shadow

One of the most reliable entry points into shadow material is emotional reactivity. Moments of disproportionate anger, jealousy, shame, defensiveness, or contempt often indicate that a shadow complex has been activated. These reactions tend to feel urgent, embodied, and difficult to regulate because they bypass conscious reasoning.

Such responses are rarely about the present situation alone. They are echoes of unresolved inner material seeking recognition. The intensity of the reaction is a clue: something old is being touched.

Careful reflection on recurring triggers can reveal patterns. You may notice specific qualities you despise in others, behaviors that evoke immediate judgment, or situations that consistently destabilize you emotionally. These experiences function as psychological mirrors, reflecting back what has been disowned.

Rather than asking, “Why did they do this to me?”, shadow work reframes the inquiry: What part of me is being touched, and why? This shift transforms conflict into information. It does not excuse harmful behavior, but it redirects attention inward, where genuine change becomes possible.

Compassionate Confrontation and Inner Dialogue

Confronting the shadow does not mean indulging destructive impulses or reliving trauma without support. It means acknowledging the psychological function these parts once served. Many shadow aspects developed as adaptive responses—strategies for protection, survival, or belonging under earlier conditions.

A child who learned that anger was dangerous may bury it deeply. An adolescent who was punished for vulnerability may armor themselves emotionally. These strategies often worked once. They simply outlived their usefulness.

Engaging the shadow through inner dialogue can be particularly effective. Whether imagined symbolically, explored through journaling, or facilitated in therapy, this dialogue allows unconscious material to articulate its unmet needs and original purpose. Questions such as What were you protecting me from? or What do you need now? can reveal unexpected tenderness beneath defensive patterns.

When approached with compassion, the shadow often reveals itself not as an enemy, but as a wounded ally—one that has been carrying emotional weight in isolation.

Integration and Psychological Maturity

Integration is the central aim of shadow work. This does not mean eliminating undesirable traits, but consciously relating to them so they no longer operate autonomously. Integration restores relationship between ego and unconscious, allowing previously split-off parts to rejoin the psyche in a regulated and conscious way.

When shadow material is integrated, psychic energy previously bound in repression becomes available for creativity, assertiveness, intimacy, and authentic self-expression. Life begins to feel less effortful, less reactive, and more intentional.

A trait once experienced as destructive—anger, for example—may reemerge as healthy boundary-setting or moral clarity. Vulnerability may transform from a source of shame into emotional depth and relational intimacy. Integration restores choice, replacing unconscious compulsion with conscious agency.

Psychological maturity is not the absence of inner conflict. It is the capacity to hold complexity without fragmentation.

Shadow Work as a Lifelong Practice

Shadow work is not a linear process or a one-time intervention. The psyche unfolds in layers, and new shadow material often emerges at different stages of life. What was invisible in early adulthood may become unavoidable in midlife. What was adaptive in one context may become limiting in another.

With continued practice, individuals typically report greater emotional regulation, reduced projection, deeper relationships, and a more grounded sense of self. There is often a quiet confidence that emerges—not performative or inflated, but rooted.

Creative expression—art, music, movement, or writing—can provide additional pathways for integration, particularly when language alone feels insufficient. Symbols often speak where words cannot.

For many, working with a Jungian-informed therapist offers essential containment and guidance, especially when navigating complex trauma or deeply entrenched patterns. Shadow work does not require isolation; in fact, it often unfolds most effectively in relationship.

Final Reflection

To engage in shadow work is to take responsibility for the full spectrum of one’s inner life. It is a commitment to psychological honesty, emotional maturity, and self-knowledge. By reclaiming what was once rejected, the individual moves closer to wholeness—not perfection, but integration.

In Jungian terms, this is not merely personal growth. It is the work of becoming who you already are.

And in that becoming, something quietly stabilizing occurs: life no longer feels like something happening to you, but something unfolding through you.

Leave a comment